Anxiety is a familiar feeling to many of us— the knot in your stomach, a flutter in your chest, sweating palms and racing thoughts— and it shows itself in different ways. As parents we may experience these intense feelings of nervousness when it comes to work, the well-being of our children, or the day to day stressors of life, and we can usually reason our way out of them with a few deep breaths and some positive thinking. When it comes to our children, though, they haven’t had the same practice in these experiences. It can be difficult for children to differentiate between “real alarms” and “false alarms,” so to them, little problems can feel just as stressful as big ones.

As invested as we may be in our children’s lives and feelings, it isn’t always easy to recognize when a child is feeling anxious. Anxiety goes beyond shyness or nervousness and lends itself to deeper, more complex feelings and experiences that are difficult to understand from an outside perspective. So how do you know if your child is feeling anxious? And how can you help?

Symptoms of Anxiety

Anxiety manifests in three ways: cognitively, physiologically, and behaviorally. Your child may experience some or all of these factors, and it’s important to know what to look out for.

Cognitive symptoms refer to the anxious thoughts that pop into your child’s head. These types of thoughts are usually “what ifs” and relate to fears of the future or the unknown:

- “Everyone will laugh at me if I don’t know the answer.”

- “What if my mom isn’t picking up the phone because something bad happened to her?”

- “They’re going to think I’m stupid.”

Physiological symptoms of anxiety refer to the physical sensations your child might feel in their body when they’re anxious. These include a range of symptoms:

- Pounding heart

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Feelings of choking or shortness of breath

- Sweating

- Feeling too hot or too cold

- Shaking or trembling

- Nausea or stomach pain

- Feeling dizzy, lightheaded, unsteady, or faint

- Numbness or tingling

- Feeling like things aren’t real or being detached from yourself

Behavioral symptoms are what your child does (or doesn’t do!) when they’re feeling anxious. These actions could look like:

- Avoiding anxiety-provoking situations (e.g. taking 5 flights of stairs instead of getting in an elevator)

- Leaving the anxiety-provoking situations (e.g. turning off your camera when called on in remote school)

- Asking for excessive reassurance (e.g. asking parents over and over, “will I be okay?”)

Understanding Anxiety

Even if you know what the symptoms of anxiety are and what to look for, you may still be wondering why your child is experiencing anxiety and how to “turn it off.” We can think of anxiety as being similar to a fire alarm. A fire alarm is designed to alert you that the building is on fire, and you’ll likely feel amped up when it goes off— you start to think that you may not be safe, your heart may start racing, and you take action by leaving the building. However, even though it’s meant to alert you that there’s a fire, there may be many other reasons why it is set off. It could be beeping because someone burnt a little popcorn, pulled the alarm unnecessarily, or simply because it is malfunctioning.

Anxiety is a natural alarm system for the body. It’s there to let us know that something might be wrong and enable us to take steps to address the situation and remain safe. It’s important to know that having anxiety isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s important that we feel anxious and react swiftly when the fire alarm goes off; it’s how we stay safe. Similarly, it is our anxiety that helps us avoid touching a hot stove, remain a safe distance from a cliff, and run away from a suspicious stranger.

But just like there are false fire alarms, there can be false anxiety alarms. Some children react with a strong sense of fear in the absence of serious danger. They may freeze up when called on in class, cry in fear about being dropped off at school, or hide in the basement when a thunderstorm is coming. In their body and mind, they feel and think there is a sense of urgency or danger. Their anxious thoughts, physical feelings, and resulting actions reinforce the belief that there is danger, even if in reality, there isn’t.

Overcoming the thoughts and feelings related to anxiety is a challenge. It requires skills and is something that children need to practice. It’s important to offer your child support, reminding them that it’s normal to feel anxious from time to time, but that they are the one who controls those experiences. Their experience does not control them!

Anxiety Disorders

While anxiety is adaptive and helpful, clinical anxiety is when the natural alarm system is out of whack. These children have a heightened alarm system; their bodies react to a situation with anxiety, even though there’s no actual danger. If they are prone to having many false alarms, or struggle to tell the difference between situations that are real alarms or false alarms, it could be an anxiety disorder.

There are several types of anxiety disorders. Generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, or separation anxiety disorder each have their own unique set of symptoms, but at their core they all involve worry, fear, or panic. The response they elicit is disproportionate to the level of danger posed by the object or situation. In reality there may be no imminent threat, but your child certainly feels that there is. In the case of an anxiety disorder these feelings start to interfere with and inhibit day-to-day functioning.

Why Does Anxiety Stick Around?

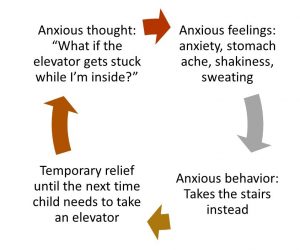

Anxiety sticks around when people get caught in an anxiety loop. Let’s look at an example of this loop with a child who is scared of elevators.

The next time the child is confronted with a situation where they need to go in an elevator, they will again look to avoid. Until the child begins to face the fear and approach rather than avoid, they cannot learn that they are unlikely to actually get stuck in the elevator.

Helping children understand the concepts of real alarms and false alarms, and the reason they continue to feel anxious, are critical to helping them conquer their fear. As we often tell our clients when it comes to treatment of anxiety, there is good news and bad news. The good news is we know what works. The bad news is that it involves facing fears, and that can be really hard. Understanding how anxiety works can help children and their parents understand their experience, take ownership of their situations, and be more willing to persevere in the next steps of therapy. To learn more about that next step, check back in two weeks as we discuss facing your fears by climbing the bravery mountain.